By CHERIAN GEORGE

The New York Times’ decision to give in to the outrage industry by declining to publish any more political cartoons reminds me of an incident half a world away, at the Indonesian news organisation, Tempo.

Needless to say, Tempo—an outspoken liberal magazine in the world’s largest Muslim nation—is no stranger to cartoon controversies. Like the Times, Tempo has had to feel its way along the precariously hazy precipice between pointed provocation and hazardous offence.

Unlike the Times, though, Tempo’s editors haven’t given up trying. One dramatic demonstration of their commitment to cartoons occurred in March 2018, after they ran this one, alluding to the leader of the Islamic Defenders Front (Front Pembelah Islam, FPI).

FPI is to the manufacture of religious indignation what Nike is to shoes. They’ve got strong brand recognition and a big chunk of the market, achieved largely through cheap labour and clever marketing. They’ve been described as a morality racket—they tend to leave you alone once a donation is deposited into the right bank account—but nobody in public life can afford to ignore them, as evidenced by their leading role in the downfall of Jakarta’s Chinese Christian governor in 2017.

So, when an angry FPI delegation showed up at Tempo’s offices on March 16, 2018, it’s safe to say that chief editor Arif Zulkifli (not to mention the cartoonist) had reason to be nervous.

It is Tempo’s practice to entertain groups with grievances about its journalism. “We believe we must be open, transparent and accountable to the public,” Arif told me when I visited in April.

So—against the advice of human rights activists, and not for the first time—FPI leaders were ushered into the meeting room and permitted their say.

Arif apologised for the impact of the cartoon on their feelings—but not for publishing it. This was enough for them, but they wanted him to repeat it to the crowd gathered outside.

He obliged, braving a parking lot overrun by FPI members, mounting their lorry and taking the mic. Arif spent several minutes defending Tempo’s policies, and apologising for the impact of the cartoon.

At one point, an FPI supporter lashed out and flung off Arif’s spectacles.

But, their performance over, the crowd dispersed.

As for the cartoonist, Yuyun Nurrachman, it was his day off when FPI came calling. “They asked to meet me,” he told me. “But the editor told them it was not necessary because it was Tempo’s decision to publish the cartoon. He took responsibility.”

Tempo still publishes Yuyun’s and other cartoonists’ work.

And Arif still has his glasses.

“They are very hardy.”

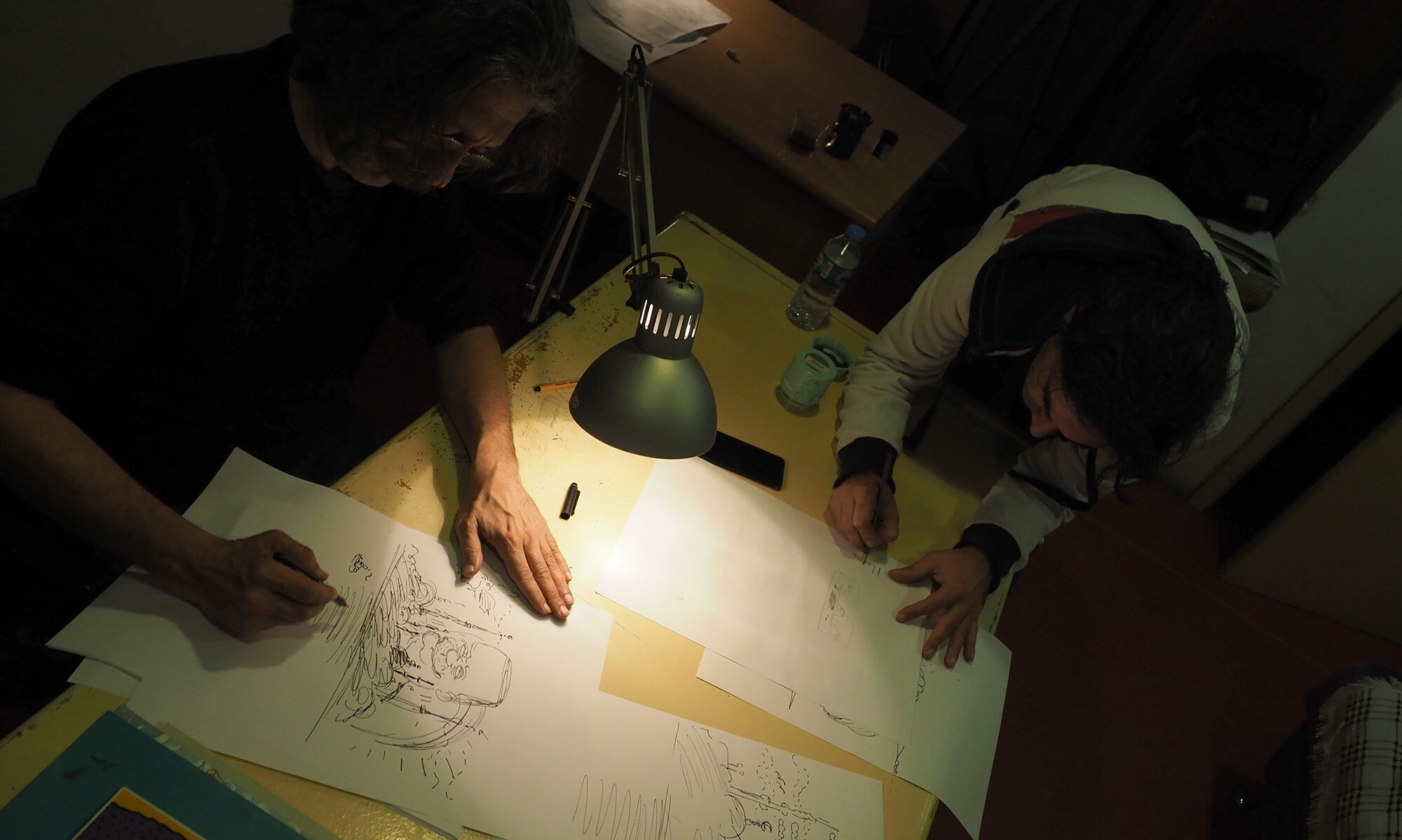

Over the past year, I’ve been interviewing many cartoonists around the world about the pressures they face. These conversations inform a book about cartoon censorship, Red Lines, that I’m working on with the Eisner-Award-winning artist Sonny Liew. (To be published by The MIT Press, it will be entirely in documentary comic book form).

The NYT controversy touches on several issues that recur in my interviews. The most obvious of them is the fact that, in many societies, the threat to cartoonists emanating from readers’ offendedness has equaled or surpassed state and religious power—for centuries the only sources of coercive censorship.

News organisations’ responses to mob pressure differ. There are those like Tempo who will defend their cartoonists’ work. There are others that are too quick to apologise, even if the cartoonist didn’t do anything wrong. Some go further and cancel or suspend the artist’s cartoons—like Ted Rall experienced when he thumbed his nose at post-9/11 patriotism.

I’ve not come across any response similar to NYT’s. Sure, during the Sri Lankan civil war, censors blocked the work of cartoonist Dasa Hapuwalana so frequently that his editors at the newspaper Dawasa decided to stop using cartoons entirely. But that was a symbol of protest against the thin-skinned—not an act of capitulation to them.

Cartoons are particularly conducive to offence-taking. Their strength is also their weakness: cartoonists’ power of visual association—making metaphorical links between different ideas—can be hijacked by readers, who can claim to see connections never intended by the artist.

Iranian cartoonist Mana Neyestani, Roberto Weil from Venezuela and Aseem Trivedi in India are among the victims of their craft’s capacity to allow unintended offence.

This is a global phenomenon, but the American variant is somewhat unique in that the attacks come from everywhere along the identity and ideological spectrums—as this new cartoon by the veteran Dutch cartoonist Joep Bertrams illustrates:

In most cases, the cartoon and its creator are not the real targets. The outrage orchestrators actually have their eyes on elite organisations that are implicated in publishing or permitting the cartoon.

In Iran, Azeri protesters probably latched onto Neyestani’s cartoon, he told me, because it appeared in a newspaper owned by the then president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Nikahang Kowsar is another Iranian cartoonist who got caught in the cross-fire, in his case between religious hardliners and moderates in government. Not that it’s any comfort to know the attacks might not be personal. Neyestani spent about three months in jail; Kowsar was sentenced to death by some Islamic jurists and had to flee the country.

Similarly, in the United States’ highly polarised ideological battleground, cartoons are often a proxy target. Activists are always looking to corner their elite opponents, and a cartoon that’s deemed offensive is well suited to such a purpose.

Take this 2017 cartoon by Matt Wuerker of the liberal news website Politico, needling Texans’ hatred of the federal government.

Conservatives, led by Fox News, pounced. “The left-leaning Politico website has taken a potshot at white southern Christians in an insulting new cartoon depicting believers as stupid and still yearning for the secession of the south,” said Breitbart.

“In the media wars, people will beat up on their rivals,” Wuerker (below) said when I visited him last month. “I’m pretty sure they saw it as an opportunity to attack Politico.”

And of course, there’s no liberal media effigy more prized than the New York Times. So perhaps it’s no wonder that its editors have decided to stop serving torch-wielding offence-takers the tinder of political cartoons.

NYT’s move is part of a larger trend—the erosion of that special, symbiotic, centuries-old relationship between cartooning and journalism.

Long before the NYT decision, that bond was being weakened by various forces, from the digital disaggregation of media products to the financial crisis of journalism. Today, we are more likely to see political cartooning allied with the creative arts, book publishing and social media than with news.

This is a loss for both sides. News media will lose an important vehicle for incisive commentary. Cartooning, too, will lose. Not just monetarily, but also ideationally. Several thoughtful cartoonists tell me how being plugged into a newsroom’s daily rhythms—and, yes, even working with demanding editors—has helped them produce better work.

In China, for example, Kuang Biao (above) treasures the period when he was working at the Southern Metropolis Daily during Chinese journalism’s “golden age” in the 1990s. He was able to see the dark side of China’s economic ascent through the eyes of his reporter colleagues. In contrast, Kuang fears, today’s young online cartoonists in China are disconnected from the ground.

There are important conversations to be had about how, in a world prone to weaponised indignation, journalism can continue to embrace the editorial cartoon as a genre. That dialogue will go on, I’m sure, in many newsrooms around the world. It’s just a shame the New York Times won’t be part of it.