With Venezuela’s political crisis making international headlines, the world has been getting a closer look at the dictatorship of Nicolas Maduro. But the tyrannical character of the regime is not news to Venezuelan cartoonist Roberto Weil, who was forced to flee his homeland in 2014.

“When you see Maduro with a tie, in front of a mic, you don’t see the guns, the mafia, behind him. These are not people with any values at all. They are real criminals,” he told me when I visited him in Miami last November.

Weil’s first run-ins were with Maduro’s predecessor, Hugo Chávez, who ruled Venezuela from 1999 until his death in 2013. “Chavismo” left-wing ideology was all about helping the workers and the poor, but that didn’t stop officials from engaging in corruption and criminality.

One of Chavez’s supporters, a host on national television, even called the cartoonist a terrorist for his critical cartoons.

But it wasn’t a hard-hitting political cartoon that turned out to be the last straw. Ironically, it was a purely innocuous piece in the Sunday magazine of a government-owned media company. In this weekly space, Weil would make light observations about everyday life, in the vein of Gary Larson’s The Far Side.

In September 2014, Weil thought it would be fun to do one about funerals.

“Family and friends at a funeral always talk about how great this person was,” he recalls about his thinking process. “I’ll draw a rat saying good things about another rat, and that’s going to make it funny, I thought.”

Weil submitted his cartoon two weeks in advance as usual, for publication in the magazine’s October 5 edition.

But on October 1, the country was rocked by the brutal assassination of a rising star in Maduro’s political establishment, Robert Serra.

Suddenly, Weil’s funeral cartoon was not so funny – it was the wrong time for morbid humour. The editors managed to stop the distribution of the magazine outside of the capital, Caracas. As for the Caracas copies, they got workers to tear out the page with the cartoon from every copy before they reach readers.

Somehow, though, the cartoon was leaked on social media. The artist and his editors explained that the cartoon had been drawn two weeks earlier and had nothing to do with Serra’s assassination. To no avail. The allegations came flying from senior figures of Maduro’s government.

“You are a miserable son of a bitch. Trash is what you are. FASCIST. This asshole makes fun of the pain of the Chavista population,” tweeted Ernesto Villegas, Governor of Aragua and former Minister of Interior and Justice.

Another even said Weil should be questioned to find out how he knew about the murder in advance. Suddenly, it was as if Weil was part of a grand conspiracy.

A week later, Maduro appeared in a televised news conference on all channels to talk about Robert Serra and his suspected killers. He introduced a video that warned the Venezuelan people about right wing opposition in their midst. Roberto Weil and his prescient cartoon flash on the screen.

Three weeks later, Weil found himself attacked by the President again. Maduro, surrounded by military officers, slammed another Weil cartoon and added that the artist was being investigated for predicting Robert Serra’s death.

The writing was on the wall. Weil fled to the United States, where he now lives.

“Nothing about the cartoon – its aesthetic, its colors, the way it’s drawn – had any connection with the horror that happened. It was a ‘cute’ cartoon,” he notes.

The incident may seem freakish. But to Weil, it was symptomatic of Chavismo’s constant need to invent enemies for its followers to rise up against. “The Maduro regime needs to describe the opposition as violent.” Even if it meant twisting a ridiculous cartoon about a rat’s funeral into a deadly conspiracy.

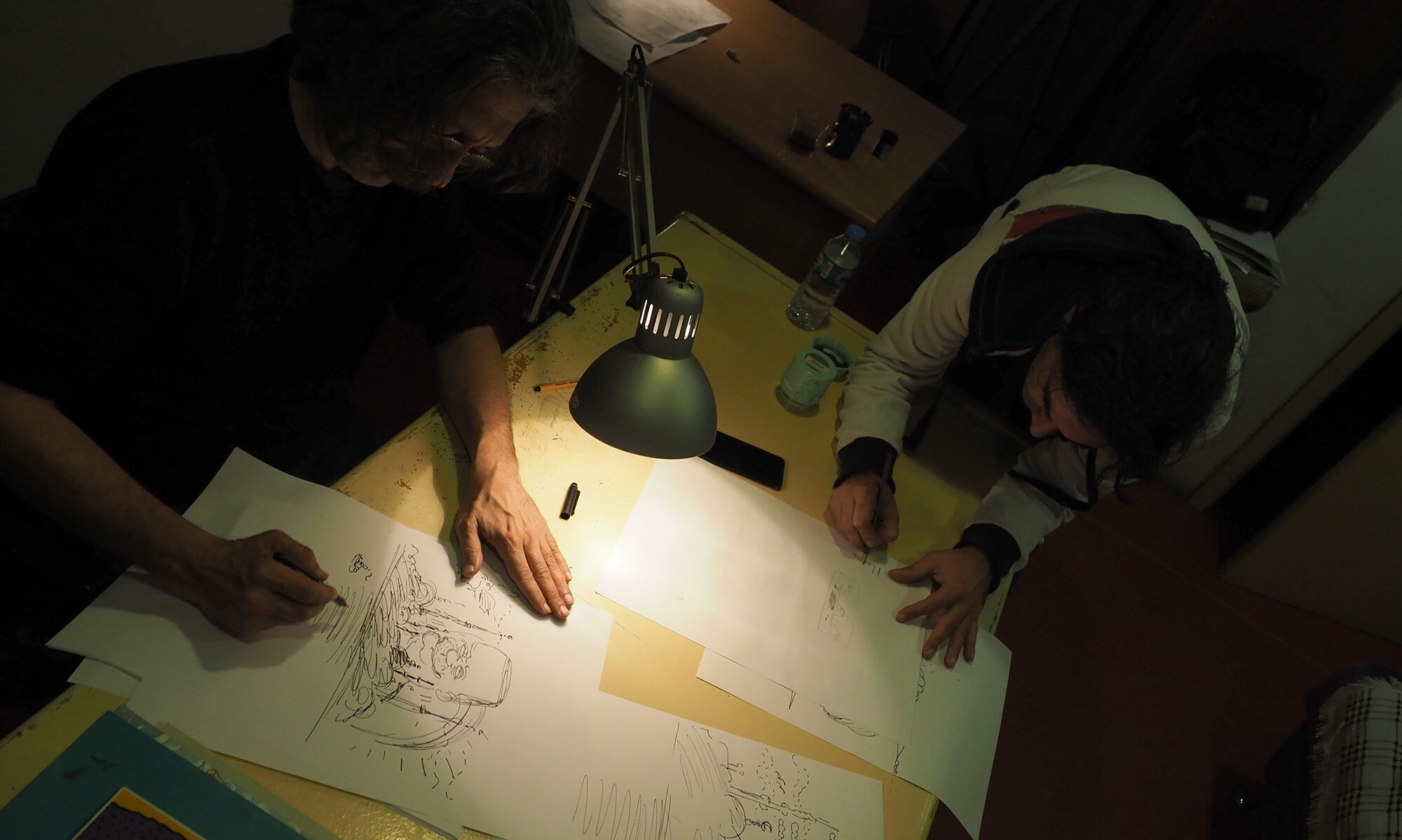

– Cherian George. This article is based on extracts from an interview with Roberto Weil for Red Lines, a book on cartoon censorship co-authored with Sonny Liew.