By CHERIAN GEORGE

This blog was written before the Singapore ban. For the latest update, please scroll to the bottom of this page.

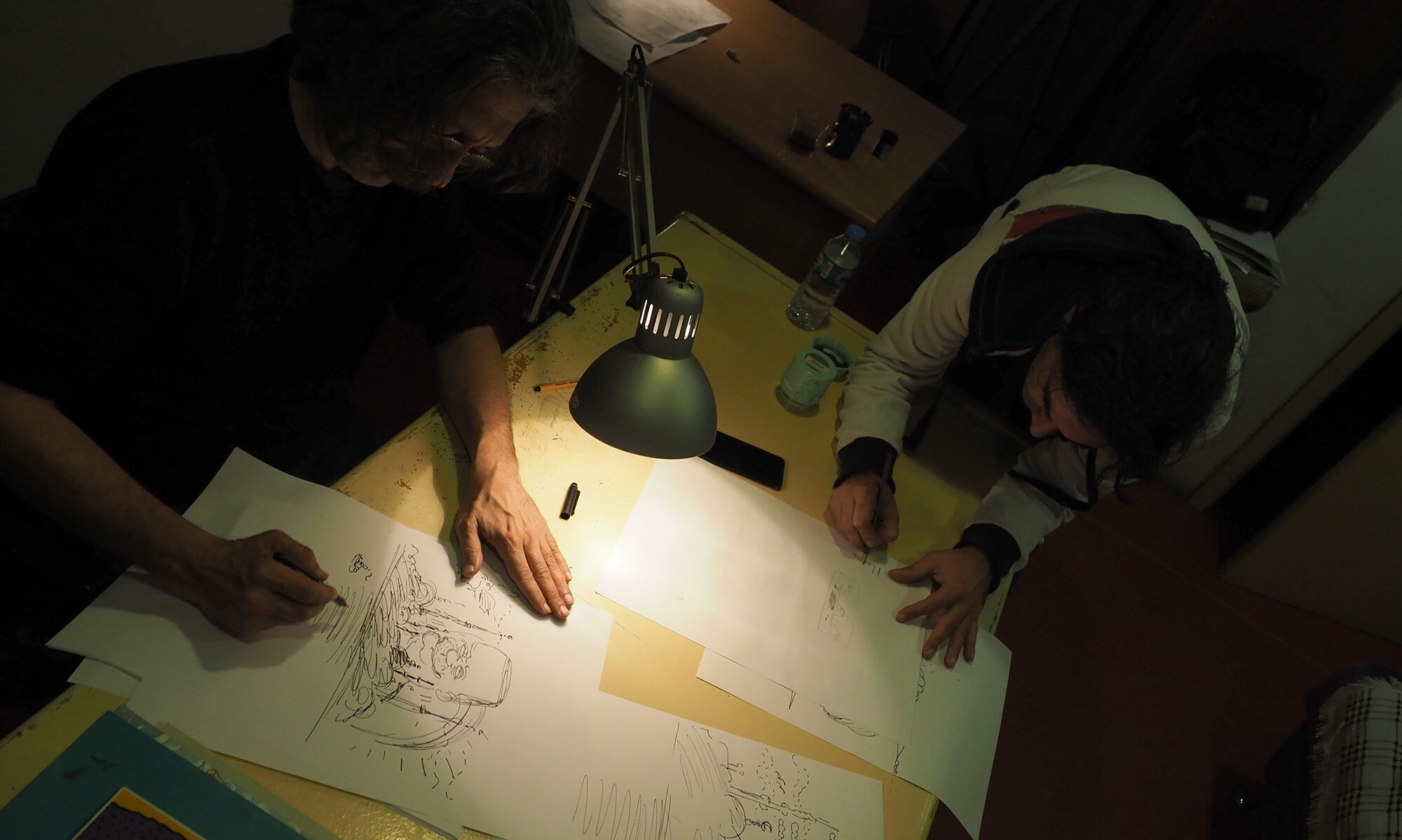

One of the ironies of writing a book about censorship is that it cannot totally escape the very forces that you are attempting to analyse. This is certainly the case with Red Lines: Political Cartoons and the Struggle against Censorship, a 450-page graphic documentary work that I produced in collaboration with artist Sonny Liew.

Obviously, when we discuss the Chinese Communist Party’s censorship practices by showing examples of censored images — such as Winnie the Pooh memes — Red Lines crosses red lines, thereby forfeiting any chance of being sold in the People’s Republic. For similar reasons, I don’t expect it will reach bookstores in another country that features prominently in the book, Iran, which is a pity considering its people’s depth of talent in and appreciation for this art form.

It never crossed my mind to spare the feelings of thin-skinned despots by redacting cartoons that lampooned them. Even if a cartoonist wildly exaggerates a leader’s flaws, the power differential between the two is so massive that a basic sense of fairness demands sympathy for the artist over the autocrat. These were the easy decisions: to display anti-authoritarian cartoons in all their disrespectful glory. So along with Boris Johnson with his head up his ass (by Morten Morland) and Donald Trump as crybaby (Anita Kunz), there’s Xi Jinping as Darth Vader (Wang Liming) and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan as a cat playing with a ball of string (Musa Kart).

Much trickier to handle are the many cartoons that were controversial for more cultural reasons. These include cartoons labelled racist, xenophobic, blasphemous, antisemitic, mysoginistic, and so on. Especially in liberal democracies, it is such cartoons that are most likely to be censored or punished, whether by the religious right or the cultural left. Many commentators have condemned religious fundamentalism, as well as political correctness or woke cancel culture, as major assaults on liberalism. If I agreed wholeheartedly with all such critiques, writing Red Lines would have been more straightforward, following in the footsteps of the many authors that have robustly defended artists’ right to offend.

But — like many of the professional cartoonists I interviewed — I don’t actually believe that cartoonists have unqualified ethical grounds, or even an unlimited legal right, to draw the first thought that comes to mind regardless of the harm this may cause. Nor does Red Lines start from the libertarian premise that all censorship is bad. It’s anchored instead in human rights doctrine, which requires that societies protect vulnerable groups from the harms of hate speech.

Alongside their reputation for cutting the powerful down to size, cartoons have a long history of sadism against the weak. As we point out in the book, they have been used in propaganda campaigns to help justify genocide, settler colonialism, slavery, war, and other assaults on humanity. Thus, cartoons have ranged from the morally courageous to the wantonly malicious. In between are many that have provoked purely unintentional offence.

Some cartoons deserve to be called out, corrected and even censored, while others are targets of manufactured outrage: many corrupt political and religious leaders, for example, are quite adept at cloaking themselves in identity politics, condemning any criticism of them as an attack on the dignity of their entire community and its beliefs.

I don’t think serious readers would disagree that all these categories exist. But the art form’s Jekyll-and-Hyde heritage — as well as the indeterminacy of many cartoons’ “true” meaning — means there’s never complete agreement about which cartoon fits in which box.

And even if we agree that something’s gratuitously offensive, there’s no consensus about how we should discuss it. The classic liberal approach is to disinfect it with sunlight: show the racist cartoon, for example, so that it can be countered. Many progressive antiracists disagree, arguing that giving such works exposure only compounds their harm, with no real benefit. The resurgence of white nationalism in liberal democracies establishes that it’s naive to assume that, in an unregulated marketplace of ideas, good speech will triumph over bad soon enough to alleviate people’s suffering.

My own view, as should be obvious from the large corpus of offensive cartoons we display in the book, is that a show-and-tell approach still has pedagogical benefits. Readers do need to be educated about cartoons that most agree crossed the line into discriminatory speech or sheer bigotry. And as for the many cases that are less clear-cut, it’s important to know the arguments on different sides, even if one remains convinced one is right.

Many of the cartoons in the book are works I would not want to see on the front page of a newspaper, as a poster in a metro station, or even Instagrammed in isolation. Context is key, and I trust our readers will see the cartoons in their intended context: deep within a substantial, serious volume that shows art that some will find offensive, not in order to offend them but to aid important discussions about freedom of expression, the responsibilities that come with it, and the ease with which cultural disputes spin out of control.

The irony, of course, is that when we ask that our book be read with the good faith in which it was written, we’re counting on a quality that the book says is in short supply. Many of the cases we describe involve expression taken out of context, and/or provoking reactions grossly out of proportion to the harms being condemned.

This risk is extreme when it comes to cartoons that offend Muslims, so we decided early on to engage in self-censorship. When a Danish newspaper published cartoons of the Prophet Mohammed as an ostentatious display of European secularism in 2005, the publicity stunt spun out of control. Opinions have since hardened. Some Europeans convinced themselves that committed liberals have a duty to blaspheme, while Muslim extremists treated depictions of the Prophet as an absolute taboo punishable by death.

Since 2006, many authors and publishers have decided to err on the side of caution to protect not only themselves but also book retailers and others in the publishing supply chain. We’ve followed that tradition, redacting the offending cartoons by strategically obscuring key details. It’s hardly an ideal resolution, because it does not do justice to Muslim readers who are capable of excercising reason and would understand the educational purpose of republication and not choose to take offence. Note that there were Muslim newspaper editors in Egypt, India, Indonesia and elsewhere who did republish offensive Prophet images along with news reports about the controversies. They did not buy the notion of absolute taboos, and trusted their Muslim readers to make contextual judgments. Such hopefulness cost some of them their jobs.

There is another serious problem with the tell-don’t-show approach. If readers know controversial cartoons only by reputation, their imaginations may run wild and exaggerate their offensiveness — or fail to picture how extreme some cartoons can be.

The chapter about the 2015 murder of Charlie Hebdo cartoonists was the toughest to write. The more I researched the topic, the more I sensed that the detractors were correct, that Charlie — whatever the intent of its artists — manifested a malicious streak in white liberal Europe. Several non-Muslim French and other Western scholars have written about this. A year before the attacks, a former Charlie Hebdo journalist penned a lengthy, damning critique of the weekly’s “obsessional” and “uninhibited” Islamophobia; and its role in normalising among the Left the idea that Islam was a “problem” for France. The cartoons he referred to included an explicit panel on Muslim women servicing terrorists as “sex jihadists”, based on a discredited news report.

Was Charlie an iconic beneficiary of France’s democratic freedoms? Yes. But was it also a model of how those freedoms should be used by adults in a democracy? Hardly. But the murders wrapped Charlie in an aura of martyrdom that obscured the distinction between these two questions, making it seem cruel and tasteless to discuss Charlie‘s tasteless cruelty.

I cited the detractors along with the magazine’s defenders. But if we did not show a single example of what the critics were talking about, the reader might think that they, and we, were just being politically correct. To penetrate the “Je suis Charlie” fog, we’d have to show, not just tell. Our starting position of total self-censorship would not do.

This is an exception that’s been adopted even by the hyper-cautious government of Singapore, where Sonny and I are from. The Singapore government generally has a zero-tolerance policy toward religious offence. With a 15% Muslim minority and large Muslim-majority neighbours, Singapore has consistently sided with Muslim countries in, for example, blocking the inflammatory anti-Muslim 2012 YouTube video Innocence of Muslims, and voting in favour of defamation of religions resolutions at the United Nations.

Yet in 2018, during parliamentary select committee hearings on online manipulation, the home affairs minister publicly displayed a shocking anti-Muslim cartoon that had been circulated by the European far right. It depicted a gang of armed and lecherous Asian, Arab and African Muslim men around a naked, bloody white woman representing Europe. Not content, the minister then posted it on his own Facebook, where the cartoon, hitherto unknown in Singapore, was viewed by at least 10,000 more people.

Obviously, by republishing the cartoon, the minister was not taking an ideological stand for free speech nor expressing support for the cartoon’s Islamophobic intent, but on the contrary trying to educate the public about the need for stronger regulation. He had to show, not just tell, because some things have to be seen to be believed. (The cartoon, as well as the minister’s comments about social media companies’ failures, appear in Red Lines.)

We’ve done our best to take into account the conflicting arguments for and against publication of dozens of provocative cartoons — showing many, redacting some, and always explaining the cultural and historical context of the work. But of course these judgments were made from a particular standpoint. As men, could we have underestimated the pain caused by viewing a cartoon such as Zapiro’s “Rape of Lady Justice”, described as the most controversial cartoon ever published in South Africa? Working with an American publisher and targeting a mainly Western market, have we sufficiently taken into account the different publishing norms and sensibilities of non-liberal societies?

I tried to correct for any blindspots by asking more than 20 readers around the world to review selected draft chapters. But while they came from diverse cultural backgrounds, they were mostly academics and probably had a professional bias in favour of open and reasoned debate.

The risk of misinterpretation remains omnipresent, especially because I’ve kept my own opinions about various cartoons between the lines. Many of the disputes I describe are highly polarised, and I’m not so naive as to think that I can persuade all readers to agree with me. In many cases I myself remain undecided about whether the cartoonist exercised enough care or should have known better; and whether reactions such as deletions and sackings were proportionate or over-the-top. My goal in many cases was merely to try to get readers to see that it is possible for reasonable people to hold strongly differing viewpoints on a cartoon. To this end, I resisted the urge to make my own pronouncements in every case.

I’m glad that perceptive reviewers have recognised this effort. In the Netherlands — a country consistently rated among the freest in the world — Tjeerd Royaards welcomed my attempt to open a “much-needed” discussion of Charlie Hebdo and why it’s important to “avoid perpetuating negative stereotypes and offending people for the wrong reason”. Writing in his Cartoon Movement blog, he said, “Immediately following the 2015 attack, it was almost impossible to condemn the attack while also being critical of the Charlie Hebdo cartoons. George does not shy away from this question, giving equal attention to defenders of Charlie Hebdo cartoons and to people that argue that the anti-Islam cartoons targeted an already stigmatized and discriminated group, French Muslims.”

Leonard Pierce, reviewing the book for The Comics Journal, praised Red Lines for its “determination to avoid simplistic moralizing”. But despite this self-restraint, or because of it, it’s perhaps inevitable that some will feel Red Lines crosses red lines.

UPDATE, 1 NOVEMBER 2021

“Book on political cartoons and censorship by Cherian George, Sonny Liew blocked by IMDA” – Yahoo News

Singapore regulators’ decision

1 November 2021, 7pm — Our book has just been blocked by regulators in Singapore. See their statement.

Our distributor Alkem had taken the initiative to approach IMDA in August for consultations, knowing that Singapore’s regulations differ from the US where the book is published. These consultations had been with our full assent. We had even been discussing with our distributor various technical means of redacting art deemed too offensive.

Although we have had no direct communications with IMDA officials, we understood from our distributor that they expressed gratitude for our cooperation, and appreciated the academic purpose of the book. IMDA recognised that the book republishes examples of controversial cartoons to illuminate ongoing debates and not to offend.

The book questions the legitimacy of a lot of today’s censorship, while arguing that some red lines are necessary, particularly against hate speech. To discuss these controversies and grey areas in depth, we wanted to show, not just tell. Even so, the book covers up some potentially inflammatory cartoons with no redeeming pedagogical benefit. Our publisher and main audience is American, but we sent our draft to a diverse panel of readers around the world as a sensitivity check.

Singapore’s regulator has opted for additional caution. We will need more time to work out whether and how we can offer Singapore readers a redacted version of Red Lines that fully and faithfully communicates the substance of the book, while addressing the regulator’s concerns about showing works that it finds ‘objectionable’.

We hope readers and media will be patient while we explore this matter. If you would like more insight into how we made our visual decisions, including about Charlie Hebdo cartoons, please read this blog that I posted last week (before we heard about IMDA’s decision).

Cherian

UPDATE, 12 JANUARY 2022

Parliament debate

12 January 2022 — The government’s ban was raised in Parliament today. A brief response:

Sonny and I decided, before our distributor approached IMDA, that we should make some redactions for copies heading to Singapore stores out of respect for local norms. We were waiting for IMDA’s inputs before doing the edits, but the government banned the book instead. We intend to proceed with the changes that we had in mind before the ban.

Cherian